The Mechanization and

Modernization Agreement

In January 1961, an agreement between the International Longshoremen's &

Warehousemen's Union (ILWU) and the Pacific Maritime Association (PMA)

changed the nature of work on the waterfront from Bellingham, Washington

to San Diego in Southern California.

The

agreement allowed ship owners and stevedoring contractors to be "freed

of restrictions on the introduction of labor-saving devices, relieved of

the use of unnecessary men and assured of the elimination of work

practices which impede the free flow of cargo or ship turnaround. The

guarantees to industry are in exchange for a series of benefits for the

workers to protect them against the impact of the machines on their

daily work or on their job security."

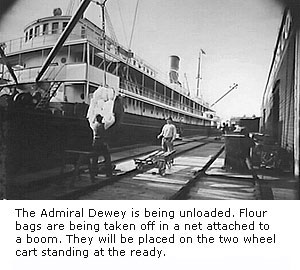

Long before the Agreement, mechanization in handling cargo began to make

longshore work easier: rope slings attached to booms on the ship lifted

heavy loads both on and off the ship, taking sacks, boxes and barrels

off the longshoreman's back. Four wheel dollies and eventually forklifts

moved cargo around on the dock and in the ship's hold. Once in the ship,

cargo was stowed by hand to take advantage of all the nooks and

crannies. A tight stow maximized the use of space, prevented cargo from

shifting during the voyage, and

Long before the Agreement, mechanization in handling cargo began to make

longshore work easier: rope slings attached to booms on the ship lifted

heavy loads both on and off the ship, taking sacks, boxes and barrels

off the longshoreman's back. Four wheel dollies and eventually forklifts

moved cargo around on the dock and in the ship's hold. Once in the ship,

cargo was stowed by hand to take advantage of all the nooks and

crannies. A tight stow maximized the use of space, prevented cargo from

shifting during the voyage, and

was the pride of the skilled longshoreman.

By the 1940s, new forms of mechanization began to significantly reduce

the number of men required to do a particular task. For example, when

raw sugar was

shipped in bags, stowed by hand and discharged sack by

sack, it required seven 10-hour shifts for five gangs of longshoremen to

unload the vessel--a total of 6,650 man hours. In 1942, sugar began to

be shipped in bulk, moving on and off the ship in huge bins on conveyor

belts. It took only 1,000 man hours to unload the ship. And in the

warehouse, 600 men were needed to handle sacks of sugar; only 200 were

needed to tend to the bulk sugar.

By the 1940s, new forms of mechanization began to significantly reduce

the number of men required to do a particular task. For example, when

raw sugar was

shipped in bags, stowed by hand and discharged sack by

sack, it required seven 10-hour shifts for five gangs of longshoremen to

unload the vessel--a total of 6,650 man hours. In 1942, sugar began to

be shipped in bulk, moving on and off the ship in huge bins on conveyor

belts. It took only 1,000 man hours to unload the ship. And in the

warehouse, 600 men were needed to handle sacks of sugar; only 200 were

needed to tend to the bulk sugar.

The Mechanization and Modernization Agreement paved the way for new

forms of mechanization, like containerization of cargo which dropped the

need for longshore work on a ship from 11,088 hours to about 850 hours.

Writers of the Agreement realized that their approach to the inevitable

loss of jobs to machines was revolutionary. While they took care of the

longshoremen then working, they didn't have all the answers for the

future. Those answers, addressing jobs and the economy of our city, are

up to us, their children.

From Otto Hagel and Louis Goldblatt, Men and Machines

"Walk Along the Water"

"Walk Along the Water"

© Oakland Museum of California, used with permission.

back

back