The Waterfront Changes Hands

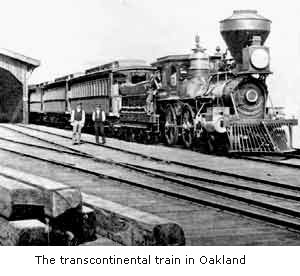

Horace Carpentier held onto Oakland's waterfront until 1868 when he sold

his control of the waterfront to the Central Pacific Railroad. His deal

with the railroad was a key element in persuading the railroad to choose

Oakland for the terminus of the transcontinental railroad. Carpentier

benefited handsomely from the deal but so did Oakland.

The

transcontinental railroad cut travel time between California and the

East Coast from 118 days to 6 days. The economic benefit for Oakland, at

the end of the rails, was enormous as travelers and freight flowed

through the city and its waterfront. Hotels, restaurants, barber shops,

drug stores and other services for travelers sprang up around the 7th

Street depot. Attracted by railroad jobs at the Central Pacific yards in

West Oakland and by business opportunities spurred by the flow of goods

and raw materials, legions of newcomers swelled the population of

Oakland which grew from 1,543 in 1860 to 34,555 in 1880.

The

transcontinental railroad cut travel time between California and the

East Coast from 118 days to 6 days. The economic benefit for Oakland, at

the end of the rails, was enormous as travelers and freight flowed

through the city and its waterfront. Hotels, restaurants, barber shops,

drug stores and other services for travelers sprang up around the 7th

Street depot. Attracted by railroad jobs at the Central Pacific yards in

West Oakland and by business opportunities spurred by the flow of goods

and raw materials, legions of newcomers swelled the population of

Oakland which grew from 1,543 in 1860 to 34,555 in 1880.

The waterfront and the railroad were closely connected. Trains traveled

straight down 7th Street to the Long Wharf that jutted two miles out

into the Bay. The Long Wharf was a hub of shipping activity with acres

of cargo sheds and hundreds of longshore jobs. Carpentier's lucrative

ferry service now belonged to the railroad. By 1877, over 4 million

passengers a year were commuting on ferries between San Francisco and

Oakland.

The railroad's economic resources, including control of Oakland's

waterfront, gave it enormous political power in the city. And the

railroad used its power to make sure its own economic interests were

served, regardless of the impact on the public good. Competitors were

not tolerated. For example, in 1893, John L. Davie launched the "Nickel

Ferry" from the Franklin St. pier in an attempt to break the railroad

monopoly on ferry service to San Francisco. But the railroad had the

resources to win in a fare war and drove Davie out of business in a

couple of years. Political opposition was not tolerated. Newspaper

accounts tell of railroad workers marched to the voting booths to follow

their employer's instructions. City politicians were regularly described

as "railroad men" who voted against any measure that might curtail

railroad profits.

The railroad's ruthless control fueled numerous attempts to oust them.

Opposition to the railroad usually met defeat. But by the end of the

century, the political forces of the Progressive Movement were

determined to break the power of Central Pacific's successor, the

Southern Pacific Railroad.

From Beth Bagwell, Oakland, The Story of a City

"Walk Along the Water"

"Walk Along the Water"

© Oakland Museum of California, used with permission.

back

back